Life is a vast concept, and the variety of forms and energies that it takes on is truly mind-blowing. It is no wonder, then, that as people have sought to understand Existence, they have been prone to separate it into different realms. Even modern science has its basic states of matter. Of course, this classifying of Life is nowhere more prominent than in religion, wherein it is referred to as cosmology—the breaking up of the greater existence into functional regions. Thus in Christianity there is the dichotomy of Heaven and Hell; Vedic religion has the Kingdom of Indra and the Kingdom of Yama; and Greek myth holds the doctrines of Tartaros and Elysium. The list goes on and on, each religion having its own understanding of the universe. Gaelic Paganism is no different: it, too, has a notion of different realms and worlds.

The cosmos of the Gael differs quite radically from those of the “mainstream” religions. This is largely due to the underlying belief in reincarnation. While the afterlife is a whole discussion unto itself, to fully understand the Gaelic cosmos, it is important for the reader to at least have a basic knowledge of post-mortem beliefs. To the Gael, then, the soul is eternal. It comes into the physical world to learn and to grow. After death, it departs to the appropriate Otherworld realm, the nature of which is based on the person’s deeds in life. After spending a while amongst the Otherworld islands, the soul returns to the physical to continue its education. This is the basic pattern of life and death which underscores the Gaelic cosmos.

On account of this idea of reincarnation, there is no concept of a permanent life within any one realm. This is very much unlike Christianity, wherein one is either eternally damned or eternally rewarded. In the Gaelic view, the soul bounces back and forth between the realms of trial, punishment, and reward. However even the notion of “punishment” is different for the Gael. In contrast to the view that punishment is meant to inflict pain and despair, in the Gaelic view, punishment can be a very good thing. Yes, it is painful; yes, it is despairing; but it is not without purpose. Punishment is a learning experience. It is the forge for the soul—taking what is weak and making it stronger. However to achieve this strength, the soul, just as the sword, must pass through the fires that torment and burn.

With all of that being said, the Gael sees the universe as being divided into three parts. These are known by various names but usually correlate to the English Land, Sky, and Sea. For the purposes of this discussion, the Irish terms Talamh (Land), Neamh (Sky), and Muir (Sea) will be used (but bear in mind that there are other possible translations). While these words do denote worldly places, it is important to understand that they are really poetical allegories that describe something much larger.

Talamh (pronounced “TAH-luhv,” Land) is the realm in which we currently live. In some circles of thought, Talamh is alternatively known as Mide—meaning “middle,” as the land is in the middle between the sea and the sky. Under either term, Talamh is understood as the land of mortality, wherein everything is born and wherein everything ultimately dies. Here nothing escapes this cycle, and when the Tuatha Dé Danann (the Gods) came to Talamh, they, too, had to eventually shed their mortal forms.

Talamh can be seen as a type of school for the soul. Through the experiences of pleasure, pain, growth, and decay in Talamh, the soul comes to better grasp the nature of the Life force. By repeated returns to the mortal realm, the soul hopes to eventually know the mysteries and the inner-workings of Existence. After this has been achieved, it is no longer necessary for the soul to return to Talamh, but it may if it so wishes.

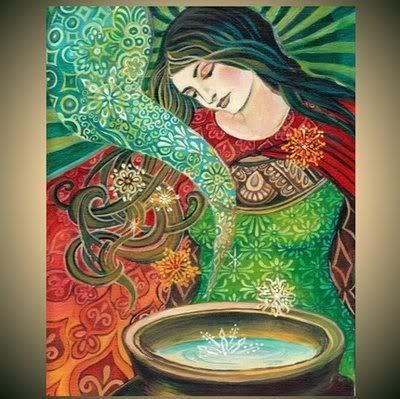

Neamh (pronounced “nyav,” Sky) is the place of the Divine. It is here that Danu stirs the Cauldron of Life, departing Existence to all things. This is the place of the Gods, and it is from Neamh that they issue their instructions and give their inspirations to humanity. As is told in Immram Brain (The Voyage of Bran Mac Febral), Neamh (here called Emain) is an absolute paradise:

9. 'Unknown is wailing or treachery

In the familiar cultivated land,

There is nothing rough or harsh,

But sweet music striking on the ear.

10. 'Without grief, without sorrow, without death,

Without any sickness, without debility,

That is the sign of Emain--

Uncommon is an equal marvel.

11.'A beauty of a wondrous land,

Whose aspects are lovely,

Whose view is a fair country,

Incomparable is its haze. [1]

If a person leads a just and upright life, then after death his/her soul is taken to Neamh, where it is free to rejoice in the splendors of perfection. While in this realm of paradise, the soul meets with the Gods and the ancestors, who in turn advise and help the soul in its development. While some souls stay in Neamh performing God-like functions (a theme that shall be explored later in this series), most, in due course, return to Talamh. After all perfection, being perfect, eventually becomes rather boring.

The final realm of the Gaelic cosmos is Muir (pronounced “mweer,” Sea). This is the land of trail and refinement, and it is in the depths of this place that the Fomhoire live, tempting humans to go against the Gods. While this realm has many different levels, it is at its deepest a place of extreme pain, sorrow, and despair.

If a person dies unjust and unrighteous then his/her soul travels to Muir. Here the soul is cleansed of its vices. How this is done depends upon how severe the offenses were. One may be forced to cry, to laugh, or to be continually slaughtered in battle. The remedies are numerous. According to this variant nature of Muir, this realm is often depicted as being composed of many different islands, each one set aside to deal with a different vice. Of course, the soul is not kept here forever. Having learned its lesson, it eventually rises above its struggle and returns to Talamh.

Defining Existence by the realms of Talamh, Neamh, and Muir is a very convenient system. Talamh is the realm of mortals; Neamh is the realm of the Gods and of perfection; and Muir is the realm of ungodliness and discord. This is an easy way to split up the different anomalies of Life. However this tripartite view, while certainly useful, is a drastic simplification. When we classify Life into these three realms, we are often compelled to think that each realm is its own, autonomous entity. This is simply not true. Existence is fluid, and thus there are no boundaries: one realm freely flows into the next.

Talamh flows into Neamh, Neamh into Muir, and Muir into Talamh. There is no clear distinction where one begins and the other ends. Thus the Immrama (accounts of Otherworldly travels) tell both of islands of suffering and islands of great joy, describing both great torments and astounding bliss. Like the gradual transition of colors in a rainbow, one thing eventually blurs into the next.

Throughout this article, I have largely avoided mentioning the Otherworld. When thinking in terms of Talamh, Neamh, and Muir, the Otherworld becomes a very problematic concept. In the mycological accounts, all sorts of beings and activities figure under this one, broad category: Gods and demons, paradise and suffering are all said to be a part of the Otherworld. In this sense, then, the Otherworld does appear as a specific realm of Life.

Rather it is better to accept the term “Otherworld” as being just that: a world other than our own physical world. By this reckoning, the Otherworld implies all of Neamh, all of Muir, and certain non-human parts of Talamh (for remember Talamh is the mortal realm, not just the “earthly” realm of man). Therefore “Otherworld” is a separate distinction from Talamh, Neamh, and Muir, and it simply refers to a realm outside our normal, human existence.

Life is a very complex and diverse function. No matter how we classify or define it, there will always be gaps and conundrums. The trick is to put it in terms that we can understand and with which can interact. To the Gaelic Pagan, these are Talamh, Neamh, and Muir, the realms of mortality, divinity, and trial. Nevertheless, in the end it will all be only poetry—a mere spinning of words and images in hopes of illuminating that which is far too great even for the sun to brighten.

Sláinte,

Bryce

The triskelion symbol is often used to represent the Gaelic cosmology

__________________________________

[1] Kuno Meyer - The Voyage of Bran, (translation), London David Nutt,1895.

[*] Image: Pandorinha3. Triskele. Photograph. Pandorinha3's Profile. Photobucket. Web. 10 Sept. 2010..

The cosmos of the Gael differs quite radically from those of the “mainstream” religions. This is largely due to the underlying belief in reincarnation. While the afterlife is a whole discussion unto itself, to fully understand the Gaelic cosmos, it is important for the reader to at least have a basic knowledge of post-mortem beliefs. To the Gael, then, the soul is eternal. It comes into the physical world to learn and to grow. After death, it departs to the appropriate Otherworld realm, the nature of which is based on the person’s deeds in life. After spending a while amongst the Otherworld islands, the soul returns to the physical to continue its education. This is the basic pattern of life and death which underscores the Gaelic cosmos.

On account of this idea of reincarnation, there is no concept of a permanent life within any one realm. This is very much unlike Christianity, wherein one is either eternally damned or eternally rewarded. In the Gaelic view, the soul bounces back and forth between the realms of trial, punishment, and reward. However even the notion of “punishment” is different for the Gael. In contrast to the view that punishment is meant to inflict pain and despair, in the Gaelic view, punishment can be a very good thing. Yes, it is painful; yes, it is despairing; but it is not without purpose. Punishment is a learning experience. It is the forge for the soul—taking what is weak and making it stronger. However to achieve this strength, the soul, just as the sword, must pass through the fires that torment and burn.

With all of that being said, the Gael sees the universe as being divided into three parts. These are known by various names but usually correlate to the English Land, Sky, and Sea. For the purposes of this discussion, the Irish terms Talamh (Land), Neamh (Sky), and Muir (Sea) will be used (but bear in mind that there are other possible translations). While these words do denote worldly places, it is important to understand that they are really poetical allegories that describe something much larger.

Talamh (pronounced “TAH-luhv,” Land) is the realm in which we currently live. In some circles of thought, Talamh is alternatively known as Mide—meaning “middle,” as the land is in the middle between the sea and the sky. Under either term, Talamh is understood as the land of mortality, wherein everything is born and wherein everything ultimately dies. Here nothing escapes this cycle, and when the Tuatha Dé Danann (the Gods) came to Talamh, they, too, had to eventually shed their mortal forms.

Talamh can be seen as a type of school for the soul. Through the experiences of pleasure, pain, growth, and decay in Talamh, the soul comes to better grasp the nature of the Life force. By repeated returns to the mortal realm, the soul hopes to eventually know the mysteries and the inner-workings of Existence. After this has been achieved, it is no longer necessary for the soul to return to Talamh, but it may if it so wishes.

Neamh (pronounced “nyav,” Sky) is the place of the Divine. It is here that Danu stirs the Cauldron of Life, departing Existence to all things. This is the place of the Gods, and it is from Neamh that they issue their instructions and give their inspirations to humanity. As is told in Immram Brain (The Voyage of Bran Mac Febral), Neamh (here called Emain) is an absolute paradise:

9. 'Unknown is wailing or treachery

In the familiar cultivated land,

There is nothing rough or harsh,

But sweet music striking on the ear.

10. 'Without grief, without sorrow, without death,

Without any sickness, without debility,

That is the sign of Emain--

Uncommon is an equal marvel.

11.'A beauty of a wondrous land,

Whose aspects are lovely,

Whose view is a fair country,

Incomparable is its haze. [1]

If a person leads a just and upright life, then after death his/her soul is taken to Neamh, where it is free to rejoice in the splendors of perfection. While in this realm of paradise, the soul meets with the Gods and the ancestors, who in turn advise and help the soul in its development. While some souls stay in Neamh performing God-like functions (a theme that shall be explored later in this series), most, in due course, return to Talamh. After all perfection, being perfect, eventually becomes rather boring.

The final realm of the Gaelic cosmos is Muir (pronounced “mweer,” Sea). This is the land of trail and refinement, and it is in the depths of this place that the Fomhoire live, tempting humans to go against the Gods. While this realm has many different levels, it is at its deepest a place of extreme pain, sorrow, and despair.

If a person dies unjust and unrighteous then his/her soul travels to Muir. Here the soul is cleansed of its vices. How this is done depends upon how severe the offenses were. One may be forced to cry, to laugh, or to be continually slaughtered in battle. The remedies are numerous. According to this variant nature of Muir, this realm is often depicted as being composed of many different islands, each one set aside to deal with a different vice. Of course, the soul is not kept here forever. Having learned its lesson, it eventually rises above its struggle and returns to Talamh.

Defining Existence by the realms of Talamh, Neamh, and Muir is a very convenient system. Talamh is the realm of mortals; Neamh is the realm of the Gods and of perfection; and Muir is the realm of ungodliness and discord. This is an easy way to split up the different anomalies of Life. However this tripartite view, while certainly useful, is a drastic simplification. When we classify Life into these three realms, we are often compelled to think that each realm is its own, autonomous entity. This is simply not true. Existence is fluid, and thus there are no boundaries: one realm freely flows into the next.

Talamh flows into Neamh, Neamh into Muir, and Muir into Talamh. There is no clear distinction where one begins and the other ends. Thus the Immrama (accounts of Otherworldly travels) tell both of islands of suffering and islands of great joy, describing both great torments and astounding bliss. Like the gradual transition of colors in a rainbow, one thing eventually blurs into the next.

Throughout this article, I have largely avoided mentioning the Otherworld. When thinking in terms of Talamh, Neamh, and Muir, the Otherworld becomes a very problematic concept. In the mycological accounts, all sorts of beings and activities figure under this one, broad category: Gods and demons, paradise and suffering are all said to be a part of the Otherworld. In this sense, then, the Otherworld does appear as a specific realm of Life.

Rather it is better to accept the term “Otherworld” as being just that: a world other than our own physical world. By this reckoning, the Otherworld implies all of Neamh, all of Muir, and certain non-human parts of Talamh (for remember Talamh is the mortal realm, not just the “earthly” realm of man). Therefore “Otherworld” is a separate distinction from Talamh, Neamh, and Muir, and it simply refers to a realm outside our normal, human existence.

Life is a very complex and diverse function. No matter how we classify or define it, there will always be gaps and conundrums. The trick is to put it in terms that we can understand and with which can interact. To the Gaelic Pagan, these are Talamh, Neamh, and Muir, the realms of mortality, divinity, and trial. Nevertheless, in the end it will all be only poetry—a mere spinning of words and images in hopes of illuminating that which is far too great even for the sun to brighten.

Sláinte,

Bryce

The triskelion symbol is often used to represent the Gaelic cosmology

__________________________________

[1] Kuno Meyer - The Voyage of Bran, (translation), London David Nutt,1895.

[*] Image: Pandorinha3. Triskele. Photograph. Pandorinha3's Profile. Photobucket. Web. 10 Sept. 2010.